Many of the concerns that I receive in consultations on health tend to be ‘details’: issues, although they may have some impact, its influence on the overall health is very low. If such supplement, if it is best to eat fruit before or after a meal, or if it is more the red tea or green… a Thousand stories that are read on the internet. But remember that 95 % of what circulates on the network is ‘rubbish’ designed to capture our attention. These are things that, in the best of cases, add up to a mere 0.5 % to our health. In contrast, most of the people do not pay attention to issues that, if handled poorly, they may subtract 30 % (by say a number) to your well-being.

The hydration (water + sodium chloride) is one of those crucial issues. Often overlooked, and I would venture to say that 99 % of people do not properly managed, despite the fact that it is one of the factors with greater impact on our health and on the quality of daily life.

Many people tell me: ‘I Pass the day without energy’, or some athletes say: ‘There are days that I feel good, but others, for no apparent reason, I find it hard even to maintain rhythms low’. Of course, this can be due to multiple and complex causes: general fatigue, poor sleep quality, poor diet, nutritional deficiencies, use of drugs, etc, however, in many cases it is simply a lack of water and/or sodium.

Let’s look at the importance of hydration and how to make sure of doing well in the day-to-day.

Water

Water is essential for our body to comply with numerous functions: it acts as a means of transport and is the main component of the blood plasma; regulates body temperature; it works as a solvent in chemical reactions; it lubricates joints and other organs; it facilitates the elimination of waste; participates in the digestion and provides structural support to the tissue (due to the intracellular water), among many other functions.

To ensure that all of these vital functions are maintained in optimum conditions, it is crucial to: 1) maintain adequate levels of water in the body, and 2) to replenish continuously the water that we lose.

How do we lose water?

- Breath: as you exhale, expel moist air. When on a cold day you see a cloud of ‘fog’ when you breathe, you are looking at the water vapor that comes out of your body and condenses in tiny droplets when come in contact with the cold air.

- Urine and stool: Our kidneys filter waste, which is then excreted in the urine, and we also lose some water through the feces, but to a lesser extent than with the urine.

- Breathability: One of the physiological processes most important to the agency is to maintain a body temperature close to 37 °C. To prevent this to rise to dangerous levels, the body dissipates heat through perspiration. Uses internal water, which absorbs the heat and is released through the pores of the skin. The cooling occurs when this water evaporates into the air, and this process happens constantly, even when we do not exercise or does not heat. However, we’re not feeling it because the water evaporates quickly when they reach the surface of the skin.

Obviously, this mechanism of transpiration works with more intensity when you do physical activity or if the outside temperature is high. If the temperature and/or intensity of the exercise are high, and this evaporation process is not enough, this is what we call sweating (accumulation of water in the skin). And, as I mentioned before, if the water accumulates and does not evaporate, there is no cooling. For this reason, the moisture makes it difficult to cooling: when there is more water in the atmosphere, reducing the evaporation capacity of our own water. With high humidity, we do not lose more water internal (that is to say, not transpiramos more); it simply sweat more (we accumulate more water on the skin because it evaporates less.

Our body is 60 % water, distributed in the following way:

– 67 % is within the cells.

– 33 % is outside the cells; of this percentage, 8 % are found in the blood plasma.

The intracellular water is ‘sacred’: the agency does not allow you to lose it. The water that is used for breathability comes from that 8 % present in the blood.

Why is it important to replenish the water we lose?

When we lose water from the blood decreases the volume of liquid in it, which affects the blood flow that reaches the organs and muscles. Therefore, less oxygen, it produces less energy and increases fatigue. This is the reason why, in terms of heat (and when not to invigorate water), our heart rate rises more than usual: the heart needs to pump faster to compensate for that deficit.

Anyway, as the day progresses, if you do not invigorate the water lost (especially on hot, humid days), this compensatory mechanism is no longer enough. If you do not invigorate water, will affect the performance of the muscles and organs. The brain sends us signs of fatigue (to reduce the activity and to save energy) and thirst (for ‘force us’ to get hydrated) and thus protect the organism.

Now comes the million dollar question:

Howmuch water we need to replenish in order not to leave the blood without it?

This is a difficult question to answer in a general way, as it depends on many factors: whether physical activity and, if so, the intensity and duration of this; the temperature and humidity of the environment; the body size of the person and, finally, its genetic. There are those who have a higher innate capacity to dissipate body heat through sweating, and others who do not. Therefore, there is not a single answer, but some general indications.

A formula that works quite well as a general orientation is the following:

0,033 x your weight in kg

This gives us a rough idea of how many litres of water do we need to eat in a day to replenish what was lost and avoid going into deficit.

Two clarifications on this formula: it is thought for 1) a day with environmental conditions, ‘normal’ heat and humidity, and 2) a day with no physical activity. If we exercise, have to add more water to compensate the loss (a topic that we’ll cover more on this later).

Another point to keep in mind is that the food will also supply water, especially fruits and vegetables. Approximately, this represents 20 % of the total water daily. For example, if you weigh 60 kg, and we need to put 2 litres of water (0,033 x 60), we should drink about 1.6 L / day, while the other 400 mL would come from the food.

Water that we lose during exercise

We already know the amount of water that we should consume in a normal day of heat/humidity and no physical activity. Now let’s look at the ‘extra’ that we need to replace if we exercise (as the body temperature increases, and the body has to sweat to avoid a dangerous over-heating).

As before, it is difficult to give a general recommendation because the amount of water lost depends on the type of exercise (intensity), the heat/humidity of the environment and the genetics of each person. However, here is another formula that can serve as orientation:

7,75 x your weight in kg

This will give you an estimate of milliliters of water that you lose (and you should replenish) for each hour of exercise.

Other two important points about this formula: it is designed to 1) days with environmental conditions, ‘normal’ heat and humidity, and 2) an exercise intensity moderate.

A trick further is to weigh yourself just before exercise, and then at the end. The difference of weight in kilograms will be (approximately) the amount of water lost in litres. It is true that the lost weight can also include some fat and glycogen (especially if the intensity is high or if there is low metabolic flexibility), but the largest part will be water.

To avoid a deficit of sodium is also key to reducing the loss of fluids. Below, we will see the importance of the sodium.

Sodium

Although we know that water is essential for hydration, in terms of the salt (sodium), we have been taught erroneously that ‘less is better’. These recommendations stem from the fear of hypertension and other cardiovascular problems, associated, among other factors, an excess of sodium in the diet of the general population, which often comes from a high consumption of products ultraprocesados and white bread (the main sources of salt for most people). As with sugar, the greater part of the salt we consume comes not from which we added directly to the food, but the ‘hidden’ in processed products.

However, those who take a food-based natural food (especially if it is low in carbohydrates, whether they exercise and even more if you make intermittent fasting) often face the opposite problem: a deficit of sodium, and a low blood pressure, which can cause fatigue, headaches, and dizziness.

Warning: The recommendations for sodium, which are presented below, are aimed at people with poor eating habits. Are not appropriate for those with cardiovascular risk, consume industrial products in excess, or have problems of high blood pressure associated with a high intake of sodium, uric acid, high homocysteine, high, sedentary lifestyle, etc

We’re going to detail.

When we lose water, we talk about dehydration. But when, in addition to water, we lose sodium, occurs hypovolemia: a decrease in blood volume. When you sweat, you lose water and sodium, and this reduction in volume affects the body more negatively than the loss of water alone. The sodium lost is extracellular, which is found in the blood plasma, like the water.

As soon as the body detects that you lose sodium and not replaced, try to keep the sodium levels in blood in balance by decreasing the volume of blood in circulation. This causes a drop in blood pressure, which can cause weakness and headaches. Who doesn’t have past, on a hot day, feeling ‘aplatanado’, without energy and with a feeling of weakness? You now know that the cause is not just the loss of water, but also sodium. And this can happen even on cold days, or normal if you take a low-salt diet.

The importance of the sodium is such that, without him, we could not live. One of the two functions for which the body needs to generate energy (the other is the contraction of the muscles) is the transport of ions (cations) of potassium and sodium through the sodium-potassium pump, a vital mechanism for the agency that transports sodium out of the cell and potassium inside. If this process should fail, we will die in a matter of seconds.

Now we come to the most important: the practical part.

How much sodium (not salt) should consume per day

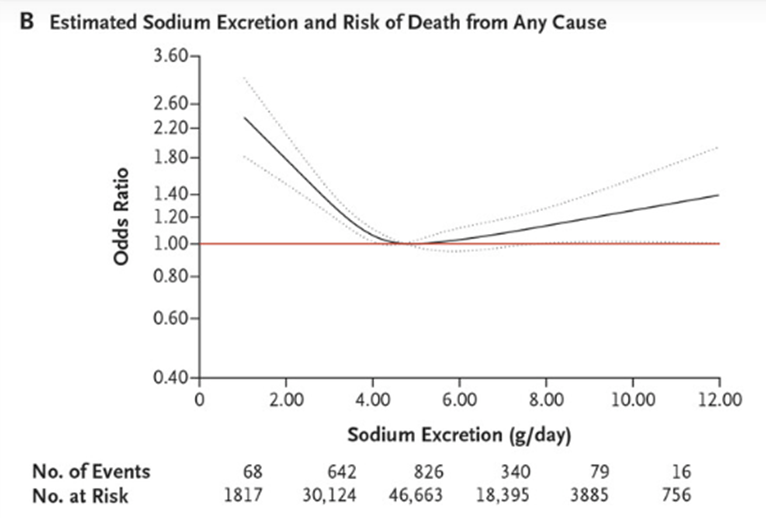

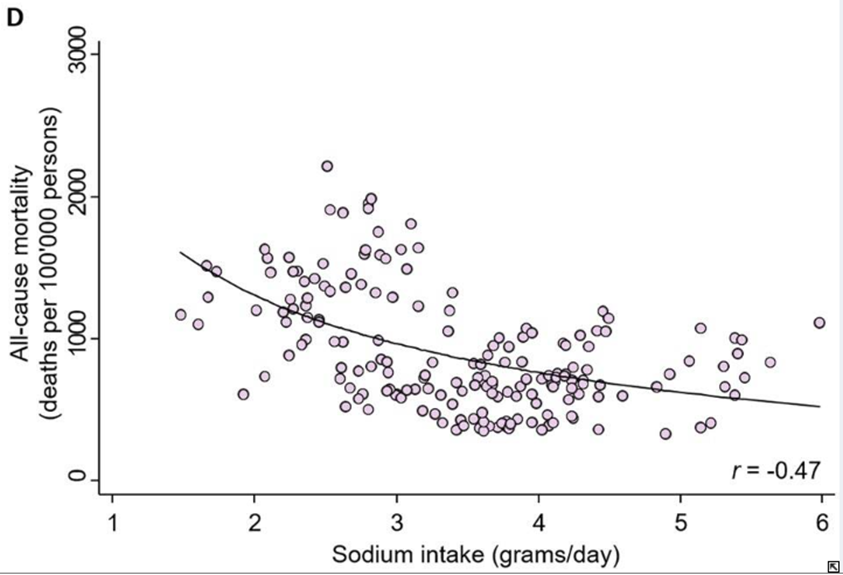

To answer this question, let’s review what science tells us up to date. The majority of the observational studies show that reducing sodium decreases the blood pressure. This is not new, and we know that it can be helpful to people who consume too much salt and you have problems of high blood pressure. However, today we focus on people healthy and normotensive (which should be avoided to decrease your blood pressure is in excess) or even hipotensas (who need to increase it). That’s why, of all the studies available, I want to highlight two that examine the consumption of sodium in relation to the lower mortality from any cause.

The first, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2014, it stands out not to be based on nutritional surveys, but in the excretion of sodium in the urine, which gives a more precise measure of consumption. The sample was large (102.000 people from 17 countries) and the follow-up to a significant (3.7 years). Their findings are clear: “a sodium intake estimated from 4 g per day was associated with a lower risk of death and cardiovascular events”. The risk increased if the consumption was below or above this amount.

The second study, conducted by the Center for Cardiovascular Swiss University Hospital of Bern in 2021, analyzed studies published since 2010, covering data from 181 countries. Their findings confirm the findings of the previous study: a daily intake of sodium 4 grams is associated with a lower all-cause mortality and a greater hope of healthy life.

As with the water, the food also contribute to sodium. If we follow a diet based on natural food, it is estimated that we consume about 1 g of sodium per day.

Let’s turn to perform calculations:

Suppose that we want to get to 4 g of sodium per day (the minimum of the range associated with the lowest mortality). If we already get 1 g through food, we would need to ingest 3 g additional sodium per day.

These calculations do not take into account the physical activity. Approximately, lost about 800 mg of sodium for every hour of moderate exercise under normal climatic conditions (1 g with heat), which should be added to the amount of sodium that we need to put if we make physical activity.

Translated into grams of salt (not sodium), which is what we really eat

It should be noted that up to now we have spoken of amounts of sodium, not salt. The salt is approximately 40 % sodium (I recommend the sea salt iodized). Translating the above calculations to grams of salt per day, the amount that we need would be:

- Calculus 1 (a day without sweat/exercise): 7.5 g of sea salt iodized (3 g of sodium).

- Calculus 2 (sweating): 10 g of sea salt iodized (4 g of sodium).

Potassium. Why I do not worry.

Unlike sodium, potassium is found inside cells. If invigorate the sodium-to lose, to keep your levels stable, potassium does not have to exit the cell to balance the levels of sodium, potassium and, therefore, do not lose.

Summary

- Water: we Should make sure to drink a day (in liters) the result of the formula: 0,033 x your weight in kg, less a 20 %, that would be the water that we get from food. If we do physical activity, you would have to add the amount of water you lose during exercise. Approximately in an hour of moderate exercise under normal weather conditions, we will lose the milliliters of water equivalent to: 7,75 x your weight in kg.

- Salt: The recommended amount of salt added is about 7 g per day, that is to say, in addition to the sodium that we get from natural foods. If we do not reach this amount, with the salt that we use for cooking (which is quite common), you can supplement other ways, for example, by adding salt to a container of water (with a little lemon juice if we want to vary the flavor) and drinking it throughout the day.

Important note: I Repeat that these calculations are aimed at healthy people with good habits: those that base their feeding on natural food, consume little bread, engage in physical exercise on a regular basis and do not have cardiovascular problems or high blood pressure. We do not want the hassle!